Ancient India

Sanskrit is the classical language of the Hindus of ancient India. Practically the whole of that extraordinary literature which began with the Vedas and culminated some time before the close of the Middle Ages, was written in Sanskrit.

Our knowledge of the earliest period is vague. The Vedas were composed perhaps before the days of Homer. Beginning perhaps about 500 B.C. and extending to about the time of Christ, is the period of the epics, during which the Mahabharata and Ramayana were probably written. Both these monumental poems are full of episodes containing at least the material for short stories.

But for the purpose of this volume, the outstanding contribution of the ancient Hindus were the fables and tales, most of which are found in large collections. The earliest of these is doubtless the Jataka, or Buddhist “birth-stories,” which were in existence at least as early as the Fourth Century B.C. The Panchatantra may be as old as the Jataka stories; both are rooted in a common source. Many centuries later an unknown author revised certain parts of the Panchatantra and produced the book known as the Hitopadesa, which may be as recent as the Fourteenth Century A.D.

Most of these stories are directly didactic, but for the historian in search of the origin of certain types, the question of the fable and its Indian or Greek origin, is one of the most fascinating in all literature. There are those who claim that the tales in the Panchatantra and the Jataka stories are the source of all the fables in the Occident, and others who believe that it was the Hindus who took the fable form from the ancient Greeks.

Of the other collections of stories the most varied is the famous Katha-sarit-Sagara, or Ocean of Streams of Stories, written about 1070 A.D. by Somadeva. This was based upon a much earlier collection, which is now lost.

The influence of the Sanskrit tales on the art of the story is almost impossible to estimate: translations and revisions of Sanskrit tales and fables were made as early as the Sixth Century B.C., and modern research is demonstrating beyond any doubt the fact that the Ancient Hindus have furnished ideas and literary forms to other nations ever since the dawn of history.

The Ass in the Lion`s Skin (Anonymous: 500 B.C.?—380 B.C.?)

The Jataka or Birth-story` ` is found in one form or another in several collections, one of which was well known as early as the Fourth Century B.C. It is a brief incident, usually in fable form, showing one incarnation of the Buddha, and drawing from the fable a little moral.

The Jataka may actually have influenced the ancient Greeks and given rise to the Jesop legends, but whether or not that is true, they constitute the “oldest, most complete, and most important collection of folk-lore extant.”

Nothing whatsoever is known of the author or authors of the particular collection from which this story is taken. It is reprinted from Buddhist Birth Stories [Nidana-Katha], by T. W. Rhys Davids, London,

1880, by permission of the publishers, Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co.

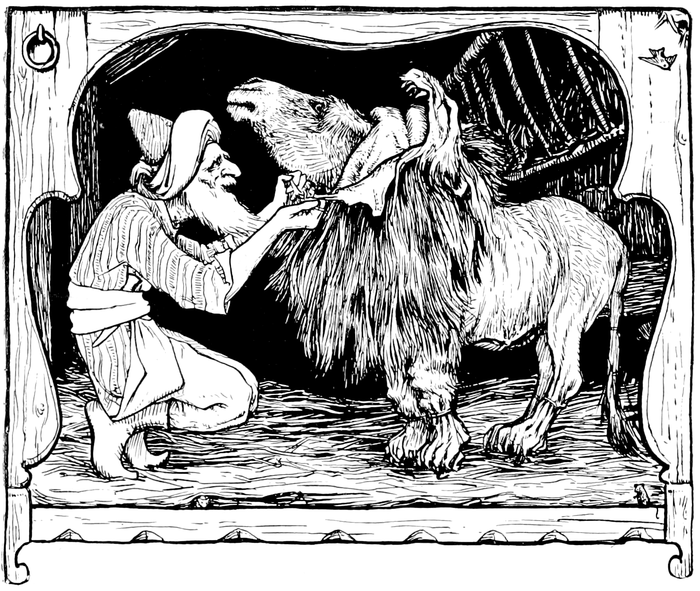

The Ass in the Lion`s Skin

Once upon a time, while Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the future Buddha was born one of a peasant family; and when he grew up, he gained his living by tilling the ground.

At that time a hawker used to go from place to place, trafficking in goods carried by an ass. Now at each place he came to, when he took the pack down from the ass`s back he used to clothe him in a lion`s skin, and turn him loose in the rice and barley-fields, and when the watchmen in the fields saw the ass, they dared not go near him, taking him for a lion. So one day the hawker stopped in a village; and while he was getting his own breakfast cooked, he dressed the ass in a lion`s skin and turned him loose in a barley-field. The watchmen in the field dared not go up to him; but going home, they published the news. Then all the villagers came out with weapons in their hands; and blowing chanks, and beating drums, they went near the field and shouted. Terrified with the fear of death, the ass uttered a cry— the cry of an ass!

And when he knew him then to be an ass, the future Buddha pronounced the first stanza

“This is not a lion`s roaring,

Nor a tiger`s, nor a panther`s;

Dressed in a lion`s skin,

`Tis a wretched ass that roars!”

But when the villagers knew the creature to be an ass, they beat him till his bones broke; and, carrying off the lion`s skin, went away. Then the hawker came, and seeing the ass fallen into so bad a plight, pronounced the second stanza:

“Long might the ass,

Clad in a lion`s skin,

Have fed on barley green,

But he brayed,

And that moment he came to ruin.”

And even while he was yet speaking the ass died on the spot!

Read More about Rose Festival

[…] The whole text can be seen on link The Ass in the Lion`s Skin. […]

Comments are closed.